Mary Renault (1905-1983) wrote six contemporary novels between 1938 and 1955 and then The Last of the Wine (1956) and the other Greek novels that are what she is best known for. Like most Renault readers I’m aware of, I came to her Greek novels first, and read her contemporary novels later. For most of my life her Greek novels have been in print and easy to find, while her contemporary novels have been almost impossible to get hold of. Now they are all available as e-books, and this makes me really happy as it means it is possible to recommend them in good conscience.

The Greek novels are historical novels set in Ancient Greece, and I love them. It’s possible to argue that they’re fantasy because the characters believe in the gods and see their hands at work in the world, but that’s a fairly feeble argument. They do however appeal to readers of fantasy and SF because they provide a completely immersive world that feels real and different and solid, and characters who completely belong in that world. I recommend them wholeheartedly to anyone who likes fantasy not because they are fantasy but because they scratch the same kind of itch. I’ve written about The Mask of Apollo and The King Must Die here on Tor.com before.

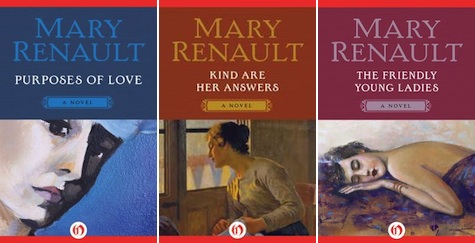

The contemporary novels (now available!) are about people being alive in Britain in the thirties and forties. They all have some kind of medical connection. (Renault was a trained nurse.) They’re mimetic novels if they’re anything, but they were published as romances. I own copies of Purposes of Love (1938) and Kind Are Her Answers (1940) that make them look like nurse novels. And in a way they are—certainly people fall in love in them, and that love is examined and central to the story. But seen in that light they are the world’s worst genre romances. I wonder what somebody who bought those copies with those covers and expecting what might reasonably be expected could possibly have thought of them?

The 1986 Penguin reissue of Purposes of Love has a line on the cover that reads “Set in the England of the thirties, a love story of extraordinary depth and power”. This is inarguably true, and it’s better than making it look like a genre romance nurse novel, but it’s still very odd.

Renault is working with a model of love that is fundamentally at odds with the model of love you find in genre romance, either in the thirties and forties when she was writing them or now. It’s also at odds with the model of love and romance generally found in the West and therefore in most Western literature, including SF and fantasy. It’s not that she has bisexual characters in absolutely all her books. Romance can be boy meets boy, or girl meets girl, just as well as boy meets girl. But if genre is anything, it’s expectations—the bargain between writer and reader won’t be betrayed. Romance has an axiom that “x meets y = eventual happy ending”. Romance makes assumptions about the value and nature of love that are very different from the assumptions Renault is using. Romances are set in a universe that works with the belief that love is a good thing that conquers all, that deserves to conquer all. Renault is starting from an axiomatic position that love is a struggle, an agon or contest—a contest between the two people as to who is going to lose by loving the other more, which certainly isn’t going to lead to inevitable happiness.

This is clearest in Purposes of Love where it’s outright stated in the last chapter:

Henceforth their relationship was fixed, she the lover, he the beloved. She believed that he would never abuse it, perhaps never wholly know it; he had a natural humility and he had his own need of her, not final like hers, but implicit in him and real. She too would hide the truth a little; for there is a kind of courtesy in such things that love lends, sometimes, when pride has been destroyed.

But she would know, always, it would always be she who would want the kiss to last longer, though she might be the first to leave hold; she for whom the times of absence would be empty, though she would often tell him how well she filled them; she who stood to lose everything in losing him, he who would keep a little of the stuff of happiness in reserve.

In the secret battle which had underlain their love, of which she only had been aware with the mind, she was now and finally the loser.

(Purposes of Love, 1938, revised 1968, from Penguin 1986 edition, p 345)

The lover is the loser, the one who cares more than pride. And this, you should note, is the happy ending, or at least the end of the book. (In its original form there was an added chapter in which they talk about having a baby—the Sweetman biography says she was forced to add that chapter, and it was removed in the revised edition. But it doesn’t substantively change anything—the book has been about two people falling in love and striving in a secret battle for who will be the lover and who the beloved.)

This struggle is also very clear in The Last of the Wine but I think it’s visible in all her love relationships. This is what love is in all of her books. And I think that it’s misunderstanding her model of love that has led to some misreadings of her books, especially The Friendly Young Ladies (1944).

Renault was a Platonist, and Plato profoundly distrusted romantic love, and especially sex. And when Plato was writing about love he was writing about love between men, and in the Greek model of homosexuality where what you have is an older man and a teenage boy, a lover and a beloved. You can see this all laid out very clearly in the speeches on love in the Phaedrus, and the Phaedrus is of course the central text and source of the title of The Charioteer (1955). Plato thought the best thing was to feel the yearning towards the soul of the other person, to love them but not to have sex with them, and the struggle he talks about is mostly about that.

Renault takes this, and adds it to Freud and the inevitability of sex (though in The Charioteer and The Last of the Wine she does write about men attempting and failing actual Platonic love—deep passionate involvement without sex) and goes on to write about characters who fall in love and have sex—male/female, male/male or female/female in different books—where the central issue of the romantic plot is which of them will lose the struggle of love and become the lover, and which will win and be the beloved. This isn’t exactly Plato, though it’s possible to see how it comes out of Plato.

It can be seen informing the relationships in The Charioteer, the other contemporaries, and indeed in the relationship between Alexander and Hephaistion (and Philip and Olympias where they keep fighting the battle) and in all of Theseus’s relationships. It’s there in all her books, when there’s a romantic relationship this contest is part of it—Alexander and Bagoas, Alexander and Roxane, even the relatively calm relationship between Simonides and Lyra. It’s not always explicit, but it’s implicit in the way the text has the world work.

Spoilers for The Friendly Young Ladies.

This is an odd book, structured oddly. The book is oddly balanced, it wrongfoots us by starting with Elsie and going on to Leo and losing interest in Elsie. If there’s something wrong with it, this is it, for me—all of Renault’s other books are quite clear about who is central and the shape of the story, even if they don’t begin in their point of view.

We’re presented with a settled couple who are bisexual and polyamorous—Leo and Helen are both women, and they both additionally date men, and on one occasion at least another woman. Helen is definitely the lover and Leo the beloved in their arrangement. Helen cares more. Helen is conventionally (for the thirties) femme, whereas Leo wears men’s clothes, writes Westerns, and thinks of herself not as a man or a woman but as a boy, although she is nearly thirty. She’s happy in her relationship with Helen, but she keeps getting involved with men she likes and then savaging them verbally either to avoid having sex with them or when her attempts to have sex with them fail, or are unfulfilling. (This isn’t as clear as it could be, I am genuinely unsure.) It’s possible that in today’s terms Leo would chose to be in some way trans.

Leo has a close male friend, Joe, with whom her relationship is boy to man. Then at the end of the book they have fulfilling male/female sex, and he writes her an odd letter asking her to go away with him, in which he explicitly addresses her as two people, the boy who he says he will sacrifice, and as “the woman who came to me out of the water.” He also sends her a very odd poem—even as a teenager who would have run away with anyone who wrote me poetry I wasn’t at all sure about that poem:

Seek not the end, it lies with the beginning

As you lie now with me

The night with cockcrow, lust with the light unsinning

Death with our ecstacy.(The Friendly Young Ladies, 1944, p.277 Virago 1984 edition)

?>

The book ends with Leo, who has been weeping “like a beaten boy” changing to weep unashamedly like a woman and packing to go away with Joe, abandoning Helen and their life.

Renault herself, in her afterword to this novel, called this ending “silly” and said it shouldn’t have been presented as a happy ending. Indeed not. But that statement would be just as true of Purposes of Love or Return to Night or North Face. If these books are taking us on an emotional journey, it’s not a journey to a conventional happy ending. The new afterword on the e-book of tFYL suggests that Renault had to give the book a heterosexual (and monogamous, though it doesn’t note that) ending for it to be acceptable in 1944. But that’s difficult to believe coming right after Renault’s own discussion of Compton Mackenzie, and also her statement that she was always as explicit as she wanted to be, not to mention what she went on to do with The Charioteer and the Greek books.

The broken Elsie-structure of the book, and the attempt to clear that up, makes it difficult to see clearly, but thinking of it in terms of contests, we have two here. In the battle between Leo and Helen, Leo has won, she is beloved. She has won before the book starts, she is the continuing victor. Poor Helen has gone off to work—and one of the strengths of this book is work mattering to people—and will return to an empty boat. In the battles between Leo and the other men, she evades the issue. In the novel’s other central battle, Peter rides roughshod over all the women he encounters, not just poor Elsie but also Norah, and he attempts to do the same to Helen and Leo—he is supremely unaware. But in the battle between Leo and Joe with erupts out of nowhere in the final chapters, Leo loses, she is forced into being the lover.

The way her tears change there makes me think of the Lisa Tuttle novelette “The Wound” (originally in the anthology Other Edens, 1987, collected in Memories of the Body 1992) which is set in a world much like ours except that everyone starts out male and when people fall in love the loser ends up with their body changing and becoming female. It’s a chilling story, and a chilling comparison.

Joe has said he will sacrifice the boy who may have Leo’s immortal soul in his keeping, and in agreeing to go, Leo is agreeing to that sacrifice. It’s not just a silly domestic arrangement, as Renault calls it, it’s terrible. And when you look at it in that light, this axiom is about exchanging independence and being a person in order to have all your happiness depend on somebody else. And this is as true for Hephaistion and Vivian and Ralph and Bagoas as it is for Leo. And that’s an odd and uncomfortable universe to live in. Can’t you love people and keep on being a whole person? Only if they love you more than you love them, apparently.

They’re brilliant books, and if you want to consider the axioms of love as part of the worldbuilding, you can have the pleasure of reading them as science fiction.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published a collection of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections and ten novels, including the Hugo and Nebula winning Among Others. Her most recent book is My Real Children. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

Welcome back. And thank you for the useful, interesting review of books that it would make my skin crawl off my bones to read.

very cool

Kate: You’re welcome! I tend to consider the axioms of romance in genre romance as part of the worldbuilding too…

It seems to me that she might also be exploring Nietzsche’s concept of “Will to Power” and how it relates to romantic relationships, though I think a deeper reading on my part would be required to see if this theory pans out.

I love Renault, especially the Alexander books. I looked for these books once, but they were indeed unavailable. I’m not sure I’m gonna read them now, the way you describe them does not sound like something I’d enjoy, it all sounds pretty depressing.

But… Do you have any plans of writing more about the Alexander books? I’d love to talk about those, I never met anyone else who read them…

I’m a big fan of all the Greek novels of Mary Renault. I’ve never read her contemporary novels, so I think I might try them.

Oh, YAY! The Alexander books are available for Kindle, as are the Theseus books.

On seeing you emphasize “weeping like a beaten boy,” I couldn’t help but think of the description of Lancelot in Malory that T.H. White talks about. (“And ever,” says Malory, “Sir Lancelot wept, as he had been a child that had been beaten.”) I think it’s probably just a coincidence, but they’re connected in my mind.

I seem to recall Renault writing somewhere (in an interview perhaps?) that what was “silly” about the ending of THE FRIENDLY YOUNG LADIES was that Leo was transformed by a single act of (heterosexual) intercourse, that this was a literary convention of the time, and that if she were doing it again it wouldn’t end the book that way. In other words, that she found that part of the book unsatisfying in retrospect.

My own take would be that the whole Joe/Leo thing reads like a bump on the log, an afterthought shoehorned into the book. The real story is a comedy of manners about Leo and Helen and how they deal with Elsie and the egrarious Peter and various secondary characters.

That book is splendid, witty and intelligent, keenly observed and emotionally honest, profoundly humane without being in the least soppy or sentimental.

The Leo-Joe stuff, not so much. If you mentally cut that out of the story, the whole novel becomes better-balanced and more satisfying.

The french say: “Un qui aime, un qui se laisse aimer”…